From the Black Atlantic to the Black Mediterranean: the sounds of quantum history

Talk by Iain Chambers delivered as part of the event “The Black Atlantic at 30: Revival and Erasure” (Institute of Advanced Studies, UCL, London, 5th of May 2023) celebrating the 30th anniversary of Paul Gilroy’s seminal book The Black Atlantic (1993)

These are simply some notes inspired by the critical sea-change induced by Paul’s The Black Atlantic. For, if Paul’s work crucially registers the racial constitution of the political economy, languages and institutions of the modern Atlantic world and the making of the West, it also does something more. It proposes a profound interrogation of what passes for history and knowledge, querying their grammar and interrogating their disciplining of the contemporary condition.

Fluid archives suspended in water sustain aquatic memories that connect bodies of water to bodies in the water: from the Black Atlantic to today’s Black Mediterranean. Registering the marine world as essential to the making of modernity—from slave ships and sea-borne empires to container logistics, the industrialised extraction of its resources (from fish to fossil fuels) and the centrality of inter-continental migration to the modern epoch—we encounter the brutal consistency of colonialism in the haunting racism that produces the violent grammar of inhospitality, today etched in the ‘hieroglyphics of the flesh’ (Hortense Spillers) on the body of the contemporary migrant.

Unlike linear chronologies and accredited histories, such rhythms and flows release the recursive dynamics of other inconclusive narratives entangled in indeterminacy and contingency. We find ourselves at sea, a little lost and uncertain beneath more expansive, wilder skies. A necessary reorientation interrupts and reworks the terra-centric Occidental template of historiography, sociology, and philosophy, puncturing their faith in rendering the world transparent to their will. It leads to what Denise Ferreira da Silva has called a moment of knowing contrary to modern knowledge, which she calls a ‘foreign language’ in her borrowing from Octavia Butler

.

And then, diving deeper into the archive, we are taken through the plantations of the Americas, Manchester cotton factories and the Atlantic coast of Africa back to the eastern Mediterranean seaboard where Italian merchants in the Balkans and medieval Black Sea ports on the steppes purchase Slavs for the slave markets of Cairo and Genoa, Venice and Naples. (Along with the thousands of slaves sold yearly in the slave market of early fifteenth-century Venice, it has recently been researched that Leonardo da Vinci’s mother, Caterina, was an enslaved person, probably captured by Mongols in the Caucasus and sold to Venetians.)

From the Black Atlantic to the Black Mediterranean, seas of dispossession and un-belonging have constantly exposed colonial modernity’s political, juridical, and onto-epistemological limits. They promote a constant critique of the possessive liberal premises of Western democracy. Today, those on the water in their small boats and dinghies, the wretched of the sea, the damned of the Mediterranean, cannot source their identity in the nation-state’s territory. Justice fails. Without papers or documents to verify their liberty, they are captives: objects reduced to the anonymous juridical space once occupied by the enslaved. Without rights, they are without an acknowledged place in the world. Waste ‘in human shape’, to borrow the phrase that Paul used to refer to those who died in the Grenfell Tower fire in 201

As Sylvia Wynter’s noted unpacking of Occidental cosmology so effectively points out, this debasement, hierarchisation and othering of human life are central to the political constitution of the modern European nation-state and its appropriation of the planet. Meanwhile, the excluded and negated sustain black holes of concentrated historical and cultural energy that continue to exist and resist. Their persistence provokes the end of a particular historical and philosophical constellation and the inauguration of another. They dub modernity, cut up its languages, remix the coordinates, and exercise their rights to live in another present and here imagine an alternative, or counter, future. And this returns us to the Gramscian and Fanonian insistence, so eloquently pursued by Stuart Hall and Paul Gilroy, that the warp and woof of culture is the fundamental texture of political life.

As the form of subaltern life today most sharply identified by Occidental law, surveillance and public discourse, the “illegal migrant” (and who decided that?), her unauthorised practices and knowledge, constructed on the move, proposes a form of political hacking that exposes all the limits of a purported democracy and its concepts of freedom and citizenship. Other equations exist, constructed and codified in the multiplicity of other bodies that matter, not simply my own. We here find ourselves in far deeper waters, offshore, drifting away from the colonising imperative of the Occidental episteme and what Ruth Gilmore Wilson powerfully calls ‘vulnerability to premature death’.

Beyond Giorgio Agamben’s noted thesis of ‘bare life’, the migrant and many others propose the exceptional state that exposes the limits of European humanism and its custody of universal rights. We are taken to the edges of the abyss to venture beyond Agamben, and much of modern philosophy, for which philosophy is the West and the West is philosophy. For the migrant, the non-white body, even if mute and lifeless, strips away the political and philosophical paradigm of Europe. Her presence interrogates my authority in the world. This explains the fear and the violence of the response.

Today, the ‘autonomy’ of those practising all the difficulties of ‘freedom’, below and beyond the brutal confines of the nation-state, bends and breaks the established frontiers of identity and citizenship. The migrant, like indigenous resistance, non-white native life and the poor of the planet, reiterates Frantz Fanon’s request to demand human behaviour from the other. We, or I, am that other. Against the limited adjustments of multi-cultural liberalism, this evokes the further skies of a radical and planetary humanism so persistently pursued in Paul’s work that, as Aimé Césaire and Fanon insisted, is to be measured against the world, not merely Europe and the West.

So, this is not simply about histories from below or presumed peripheries reconfiguring the centres of power and their languages. On the contrary, introducing non-authorised coordinates, bodies, and lives forces us to acknowledge the violent denial that constitutes our present; that is, query the temporality and terminology of the inherited narrative and its institutional pedagogies. Rather than an adjustment through the recovery of the resistance and the refused, we confront a further radical undoing and reconfiguration of what we understand by terms such as history, documents, archives, testimony, genocide and memory as we ask who has the right to narrate, define, direct and explain… to have rights.

Myths of neutrality unwind and evaporate. In its place, the open and precarious practice of registration subverts the distancing logic and control of colonised representation.

This undoing of our usual understandings of time and space, history and geography, as they speak again and are folded into further accountings of life, place and death, produce what Paul in The Black Atlantic called a ‘rhizomorphic, fractal structure’ (4). Or, as Sun Ra put it, ‘Change your time to the unknown factor’. This is the mobile composition and altogether less guaranteed spacetime of what I would call quantum history. It is where the colonial clock is contested and interrupted by other times, by the temporalities, rhythms and pace of others.

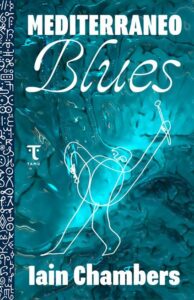

I will now use the rest of my time deploying a language dear to all of Paul’s dauntingly erudite research and writing: music, to sound out the emergence of a contemporary Black Mediterranean. In different ways, we both understand music not as a simple illustration of historical processes seemingly occurring elsewhere or as a symptom of pre-existing cultural forces and relations but rather as a transforming and critical language in its own right.

Within it lies the deeper pursuit of displacing the ocular hegemony of white sight (Nicholas Mirzoeff) with subaltern, black sounds. Once again, challenging disciplinary borders so as not to propose the history or sociology of music, but music as history, as sociology. Not to think in the boring Kantian manner of music as an abstract object of study and seek to render sound transparent to universal knowledge, but to decompose that imposition by thinking with music as practice, process and proposition.

Mediterranean musicality permits us to travel in spaces and temporalities that precede and exceed the disciplinary logic and methodologies of the modern nation-state. They produce less linear understandings of spacetime and more stratified and ragged maps. These do not simply mirror a unique will to power. Sustained in sound, this critical opening muddies the illusory transparency of transcendental Occidental rationality.

In the gaps, sliding between the authorised notes, bending and distorting the dominant cultural arrangement so that other cultures and histories voice other Mediterraneans, reasoning is freed from the singular temporality of unilateral modernity. Instead, it leads to further understandings of the making and becoming of a Mediterranean lived otherwise.

Mediterranean blues, where the scales and alternative tonalities, drawn from Islam and the Arab and Ottoman worlds, from Africa and Asia, historically and culturally mingle with the sounds of the diasporas of the Black Atlantic. The hint of a cry (think of Arab song, flamenco, Neapolitan vocals, fado and rebetika), the nasal intonations, the dark, rough granular texture, the insistence on melisma rather than a distinct intonation, the voice on edge, close to breakdown, registers the body in the sounds of a distinctive Mediterranean musicality.

Consider the famous rebetika singer Rosa Eskenazi, a Turkish-speaking Sephardic Jew born in Istanbul and raised in Thessaloniki and Athens. Rosa perfected her art in the taverns of Piraeus, singing in Greek, Turkish, Arabic, Hebrew, Italian, Ladino and Armenian. At the height of her fame in the 1930s, she recorded in Athens and Istanbul. Her biography is only one of the multiple musical maps transmitted around the Mediterranean where to paraphrase Ralph Ellison; one loses one’s identity to find it.

Consider the famous rebetika singer Rosa Eskenazi, a Turkish-speaking Sephardic Jew born in Istanbul and raised in Thessaloniki and Athens. Rosa perfected her art in the taverns of Piraeus, singing in Greek, Turkish, Arabic, Hebrew, Italian, Ladino and Armenian. At the height of her fame in the 1930s, she recorded in Athens and Istanbul. Her biography is only one of the multiple musical maps transmitted around the Mediterranean where to paraphrase Ralph Ellison; one loses one’s identity to find it.

Such sounds, their musical mixture and continual creolisation, allow us to think with music creating folds in time. Condensed in sound, in its contemporary performance, are sonic archives that interrupt the crushing institutionalisation of historical time and disturb the chronologies. To elaborate on a past to be registered, we confront what returns us to Paul’s ‘back to the future’. Like the presence of the contemporary migrant, such sounds reopen the violent archives of the colonial constitution of the present. Both disturb and interrogate a singular telling. More than a simple counter-narrative, these deeper histories propose the dispersion and undoing of the hegemonic premises that seek to fill in the details, frame the picture and conclude the story.

There is so much music I would love to play to sustain this argument on the ongoing composition of another Mediterranean spacetime. However, here I, too, remain trapped in the consequences of a linear order!

So, let’s experience this possibility just for a few minutes by listening to a piece of music sung in the most widely spoken language (in all of its variants and dialects) of the Mediterranean: Arabic. Here distinctions between high and popular culture fall away: The famous Egyptian singer Uum Kalthuum set modern poetry to music, then transmitted through the Arab world by radio and audio cassettes to a largely illiterate audience. And the music we are about to hear also sustains other historical echoes not distant from the European shore: flamenco, Neapolitan song, and re-betiko. We hear this in the shared minor keys and micro-tonalities of what today is a subaltern Mediterranean becoming black (Achille Mbembe).

To listen to the Palestinian singer and ‘ud player Kamilya Jubran and the constant return of never the same sung over improvised patterns on her ‘ud (the instrument of philosophy), we hear an aesthetics that sustains ethics, its poetics, a politics. We are invited to re-orientate understandings and confront a more complex and open reception of the formation of a modernity that is never merely mine, ours, or yours.

Qawafel

To draw a phrase from The Black Atlantic and conclude: what we have just heard engages us with ‘an enhanced mode of communication beyond the petty power of words…’ (p.76).

This requires listening and learning from a new set of genuinely trans-disciplinary and historical coordinates sustained by a sociology of the imagination, quantum history, ‘the fictive work of theory’ (Katherine McKittrick), and the ‘force of black speculative vision and practice’ (Jayna Brown). All of which are amplified in Paul’s writing and research. The illusory guarantees of theoretical architectures dependent on accumulative linearity, the universalisation of their premises, and the violence of their exercise are pushed out of joint. We are encouraged to step outside, contest control, escape… listen… respond… dance… and while seeking with Jimi Hendrix to kiss the sky, become accountable for the always incomplete, even incomprehensible, composition of another spacetime.

Thank you, Paul.