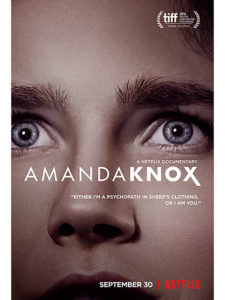

Di chi è il documentario? Di chi è la verità? Chi è colpevole e chi vittima? Chi è protagonista di questa narrazione? In che rapporto è con la verità? E con il realismo? Questo film, il titolo, il trailer, tutto si posiziona nel punto di vista di Amanda. Dopo Guedé, dopo Sollecito, anche Knox utilizza la televisione come dispositivo di produzione di verità. Una verità non definitiva, ma sicuramente più vera di quella delle aule processuali e del primo clamore mediatico. Il realismo della televisione produce una verità che è universale ed assoluta, cioè assolutamente vera fino a quando un’altra non prende il sopravvento, che non ammette contraddizione all’interno della comunità che la condivide. In questo senso la televisione produce un regime di verità, ma anche comunità; allo stesso tempo le comunità producono la televisione stessa, rendendo reciproco questo lavoro di chi plasma e chi è plasmato. Guedé ha la sua verità, universale ed assoluta, condivisa dalla comunità di Leosiners, un pubblico un po’ più ampio, più giovane, più social di quello che solitamente guarda Rai3. Certamente un pubblico di italian* disponibili a cercare tra l’inopinabilità degli atti processuali la verità di un giovane nero condannato perché più sfigato degli altri coimputati. Sollecito ha la sua verità e la condivide con un altro pubblico di italiani, forse più di italiane, che stirano guardando la televisione il pomeriggio (l’espressione è di Barbara D’Urso in persona che continua ad invisibilizzare la mia presenza davanti allo schermo!). La verità di Knox, invece, non punta alla sua assoluzione, ma alla condanna di chiunque altr*, compresa me che guardo lo schermo. Questa verità è condivisa da un pubblico di cui è difficile tracciare un unico profilo, sicuramente non nazionale, ed è l’unica tra queste narrazioni che rimette al centro la vicenda nella sua prospettiva internazionale. La cosa che colpisce, infatti, è l’ipersessualizzazione della studentessa americana-dolce-vita (Foxy Knoxy) nell’Europa che la vuole carnefice ad ogni costo e la speculare vittimizzazione di cui ha goduto negli Stati Uniti. Il film mette al centro questa divergenza prendendosi una rivincita nel mettere in scena la grossolanità del sessismo del vecchio continente ricordando anche il ruolo dei media inglesi che rivolsero grande attenzione alla dimensione più scandalistica della vicenda. Per inciso, questa verità è oggetto di proprietà, da un lato dunque il punto di vista si trasforma in una proprietà: la verità DI Guedé, DI Sollecito, DI Knox, la verità DI quella e quell’altra comunità. Dall’altro lato una proprietà, che in quanto tale, ha un valore e può essere venduta come un bene. Guardando gli acquirenti è evidente quanto valga la verità di Guedé, quanto sia bravo a venderla Sollecito con libri e comparsate, mentre il film mostra quanto valga economicamente la verità di Amanda. In una delle sequenze interviene suo padre per aiutarla ad affrontare giornalisti e paparazzi che non le danno tregua. Gli “avventori” lo incalzano ricordandogli che col tempo qualunque dichiarazione della giovane varrà sempre meno; lui sembra non comprendere. Oggi l’introduzione di questa scena nel film prodotto e distribuito da Netflix ha il valore di uno sberleffo!

I titoli di giornali e tabloid passano sullo schermo riproponendo l’aggressività con cui viene caratterizzata la sessualità predatoria di Amanda, una sadica manipolatrice che avrebbe sacrificato la coinquilina inglese. Questa ricostruzione stride con il romanzo a tinte rosa confetto (come il suo golfino) con cui viene raccontata la tenera storia d’amore tra Amanda e Raffaele. Lei negli anni ha acquistato fascino e candore, lui sembra ringiovanito e molto meno macho rispetto al codino gelatinato di Domenica5: sfiora la sua chioma bionda più con imbarazzo che con vezzo, mentre esprime l’incredulità che la bella straniera possa aver guardato proprio lui, la speranza che possa baciarla davanti al panorama più bello e il finale felice di quella magica serata. Stacco. Colombi contro luce al tramonto che si scambiano effusioni formando un cuore. “Che americanata” chiosa mia madre. Due giovani teneri e scapestrati, che si fanno qualche cannetta per togliere l’imbarazzo e passare dalle letture alle coccoline, mentre altrove, nella villetta, si consuma il lugubre supplizio della giovane studentessa inglese. Perugia, tra gli sbandieratori, i colli e i panorami è il tropico italiano. In più momenti tornano delle immagini di scogliere, case bianche e mari blu. “Mamma arò sta stu mare a Perugia?” “No quello Sollecito è Pugliese”; quel mare crea un contrasto con lo specchio di piombo in cui Knox troverà pace. Le immagini inoltre restituiscono altro che non mi era mai stato raccontato e anche qui è taciuto: Meredith non era solo la mora contro la bionda era la mora inteso come soggetto razzializzato. Lo capisco guardando sua madre, ricostruisco ad intuito la biografia meticcia che non ha avuto parola in nessuna delle narrazioni della vicenda. Sollecito e Knox sin dal primo momento danno in pasto ai media, Patrick Lumumba, così come a rimanere in carcere, unico colpevole di un delitto che non conosce giustizia è Rudy Guedé. Mentre la negritudine è al centro della narrazione di chi accusa e difende Guedé, il mostro, rimane nel silenzio la trasparenza di Meredith, forse per non togliere candore ad entrambe le studentesse rimaste invischiate in una storia lussuriosa più grande di loro, in cui sono tutte vittime.

Ritorniamo all’inizio. Il documentario è il film di Amanda, sicuramente lei non è la colpevole, comunque non la sola, vittima di una vicenda mediatica, narratrice di questa verità. Poi ci sono i protagonisti della messa in scena Giuliano Mignini, aka l’investigatore, uomo di Dio, padre di famiglia, con la passione per Sherlok Holmes e Nick Pisa, aka il giornalista narcisista, ricostruisce la vicenda come un’enorme montatura mediatica, dipinge i tratti dell’esotico italiano dove la procura ci tiene a “fare bella figura”, i poliziotti pensano “caspita un giornalista si è rivolto a me” e ottenere uno scoop in questo modo è “fantastico come fare sesso”. Due archetipi del vecchio continente: la grossolanità e il pressappochismo tipico italiano, con cui sono state condotte le indagini; l’aggressività tipica dei tabloid inglesi, con cui è stata raccontata l’intera vicenda. Osservatori privilegiati del tempo, in carico dei documenti ufficiali, protagonisti della restituzione pubblica e mediatica dei “fatti”, ma anche gli unici attori del documentario che non si limitano a narrare, ma anche a recitare, rendendo confusi e diluiti i confini tra la fiction e la puntuale ricostruzione degli eventi. In questa cornice l’unica storia narrabile è la rivalità tra donne e l’intrigo sessuale, ciò dà appeal alla vicenda, il racconto che riscrive la verità. Così le prove circostanziali, i bacetti tra Knox e Sollecito, lo sguardo algido di Amanda, vengono narrate come le uniche prove a trascinarla sul banco d’accusa. Dopo che la giustizia è ristabilita, confondendo l’innocenza con l’insufficienza di prove, la drammaticità catartica della scena finale – in cui Amanda si allontana nel mare lasciandosi alle spalle la città e i brutti ricordi – diviene subito grottesca nei titoli finali: Knox si è laureata, Sollecito è opinionista televisivo, Mignini e Pisa hanno ottenuto un avanzamento di carriera… perfino Guedé ha ottenuto un permesso premio!

all’inizio. Il documentario è il film di Amanda, sicuramente lei non è la colpevole, comunque non la sola, vittima di una vicenda mediatica, narratrice di questa verità. Poi ci sono i protagonisti della messa in scena Giuliano Mignini, aka l’investigatore, uomo di Dio, padre di famiglia, con la passione per Sherlok Holmes e Nick Pisa, aka il giornalista narcisista, ricostruisce la vicenda come un’enorme montatura mediatica, dipinge i tratti dell’esotico italiano dove la procura ci tiene a “fare bella figura”, i poliziotti pensano “caspita un giornalista si è rivolto a me” e ottenere uno scoop in questo modo è “fantastico come fare sesso”. Due archetipi del vecchio continente: la grossolanità e il pressappochismo tipico italiano, con cui sono state condotte le indagini; l’aggressività tipica dei tabloid inglesi, con cui è stata raccontata l’intera vicenda. Osservatori privilegiati del tempo, in carico dei documenti ufficiali, protagonisti della restituzione pubblica e mediatica dei “fatti”, ma anche gli unici attori del documentario che non si limitano a narrare, ma anche a recitare, rendendo confusi e diluiti i confini tra la fiction e la puntuale ricostruzione degli eventi. In questa cornice l’unica storia narrabile è la rivalità tra donne e l’intrigo sessuale, ciò dà appeal alla vicenda, il racconto che riscrive la verità. Così le prove circostanziali, i bacetti tra Knox e Sollecito, lo sguardo algido di Amanda, vengono narrate come le uniche prove a trascinarla sul banco d’accusa. Dopo che la giustizia è ristabilita, confondendo l’innocenza con l’insufficienza di prove, la drammaticità catartica della scena finale – in cui Amanda si allontana nel mare lasciandosi alle spalle la città e i brutti ricordi – diviene subito grottesca nei titoli finali: Knox si è laureata, Sollecito è opinionista televisivo, Mignini e Pisa hanno ottenuto un avanzamento di carriera… perfino Guedé ha ottenuto un permesso premio!

La verità di Amanda è una verità caratterizzata da un forte grado di entropia, in cui i dubbi servono più delle certezze per affermare una giustizia che in fin dei conti sembra premiare tutti. Ma soprattutto la verità di Amanda è la verità di Netflix, il potere di produzione e distribuzione di egemonia della narrazione, in cui i mezzi non servono solo a plasmare la verosimiglianza del racconto ma ad affermarla in comunità transnazionali, mobili che si raccolgono di volta in volta in modo fluido intorno a delle narrazioni piuttosto che nell’identità del pubblico di affezionati.